- Home

- Jonathan Maberry

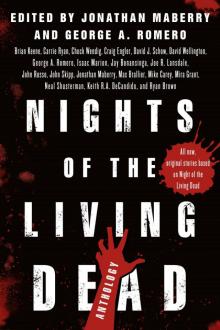

Nights of the Living Dead

Nights of the Living Dead Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Editors

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

St. Martin’s Press ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on Jonathan Maberry, click here.

For email updates on George A. Romero, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

This book is dedicated to John Skipp, who made “zombie literature” possible with his landmark anthology Book of the Dead (co-edited by Craig Spector).

You’ll always be our pal, Skipp.

From Jonathan: And, as always, for Sara Jo

From George: For Suzanne Desrocher/Romero

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks to George Romero and John A. Russo for writing the script for Night of the Living Dead and thereby lighting the fuse to something that would blow up bigger than anyone could have foreseen. Thanks to Michael Homler at St. Martin’s Griffin for going to bat for this project. Thanks to our agents, Sara Crowe and David Gersh, for guiding this project through the weird and dangerous landscape that is modern publishing. Thanks to Dana Fredsti for being the world’s best evil assistant.

NIGHTS OF THE LIVING DEAD

An Introduction

Fifty years ago I was able to convince several friends of mine that we might be able to make a movie … a real, honest-to-god motion picture, feature length.

We were in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, at the time. No one in Pittsburgh had ever made a movie before. Born and raised in New York City … (Parkchester, the Bronx) … I was around during those terrible days of gangs like the “Sharks” and the “Jets.” In my neighborhood, the “Golden Guineas” ruled the streets. This was an Italian gang. I was thought of as a “Spic.” So my ass was frequently kicked around.

My father was the greatest guy in the world. When I was comin’ up, he worked three jobs in order to “see me through.” (I was an only child.)

This “greatest guy in the world” considered himself to be a Castilian Spaniard. His family was from La Coruna. His mom and dad went to Cuba during its heyday. Finding success, they sent my father and his brothers to New York City. My father met a Lithuanian woman, Ann Dvorsky, and they married. I grew up speaking neither Spanish nor Lithuanian … strictly English … American English … New York English … Bronx English.

The Italians in the neighborhood spoke the same … Bronx English … but because of my name, Romero, they figured me to be a “Spic.” (These days, my name is often thought of as being Italian in origin. When I was comin’ up Cesar Romero was a big star. No question. I was a Latino.)

But I was only half Latino, right? And, according to my father, I had no Latino blood in me at all! Because, in those days, “Latino” meant “Puerto Rican.” To my embarrassment, my father, a Spaniard, refused to associate himself with those “bastard Puerto Ricans” who were turning New York into a “SEWER!”

So, as you might imagine, “labels” never meant very much to me.

When, years later, John Russo and I collaborated on the screenplay for my first film, we never described our principal character as being a man of color. In our minds, when we were writing the character, he was a “white guy.” An African American, Duane Jones, auditioned for the role and was, hands down, the best, within reach of our puny budget, to play it.

We didn’t change the script. Duane, himself, adjusted some of the dialogue to make the character seem a bit less “truck-driver gruff” than the way John and I had originally written him, but none of the story’s intentions were disturbed. The character of Ben met the same tragic end when, in our minds, he was white as he did when he became black. It was an “accident of birth,” so to speak.

* * *

When Russ Streiner and I were driving to New York with the very first print of Night of the Living Dead (then called Night of the Flesheaters) in the trunk of the car, we heard, somewhere along the Pennsylvania Turnpike, that Martin Luther King had been assassinated. After that … and forever after … our film has come to be viewed as a racial statement. We never intended “race” to be the film’s reason for being. We intended it to revolve around a small group of characters who, when caught in an extraordinary circumstance, find it impossible to reconcile their differences and, as a result, bring about their own demise.

To this day, I believe the film’s success to be largely a matter of misinterpretation. We got lucky. And our luck continues.

Zombies have earned a place among the “Famous Monsters of Filmland.” They’ve been around for a long time. I Walked with a Zombie, White Zombie, even Abbott and Costello met a zombie or two. When John and I were writing Night, we never thought of our “monsters” as “zombies.” We never called them zombies. In our minds, the dead were mysteriously coming back to life and eating the flesh of the living. We called them “ghouls.” Only after much had been written about Night being a “seminal” piece of cinema, and after hundreds of articles that referred to our creatures as “zombies,” did I concede the definition. Ten years after the release of Night, I wrote and directed a sequel, Dawn of the Dead, in which I first used the word “zombie.”

Today the zombie runs rampant through our popular culture. I am honored that I am considered to be the “godfather” of the zombie genre.

I can’t appropriately express how proud I am to be considered among so many greats who came before. I have devoted my life to film, and in that way I can feel justified for the kudos I’ve received over the years, but the title godfather of the zombie genre seems undeserved. It came to me as a stroke of luck.

Nonetheless, I love the genre and I always have. I feel privileged to be a participant. I feel privileged to have been asked to write this introduction to a collection of stories by authors who came to the genre not by accident but by design. I will forever be grateful for the curious circumstances that brought me to this position … one that enables me to present the works of all the worthy fiction writers whose names appear in the following pages.

—GEORGE A. ROMERO

REFLECTIONS OF A WEIRD LITTLE KID IN A CONDEMNED MOVIE HOUSE

An Introduction

I have a great deal of affection for our life-impaired fellow citizens.

Zombies. Ghouls. Walkers. Call ’em what you want. I love them with a great and abiding passion.

Really. Nothing but love.

My association with them goes way back, too. When I was ten years old my buddy Jim and I snuck into the old Midway movie theater on a crisp October night in 1968 to see a brand-new horror movie called Night of the Living Dead. It was the premiere of the flick and so far all we’d seen was one movie trailer the week before. It looked like it might be scary. But we’d been disappointed too many times to expect much. We were inner-city kids and we’d seen every Universal, RKO, and Hammer Horror flick on offer. The old stuff and the new. We were tough kids, too, because it was a tough neighborhood. Lots of violence, racial intolerance, domestic abuse, gang fights. Very few cinematic horrors actually offered anything more than escapism. Nothing could really scare us.

So we thought.

You see, after seeing all of those vampire flicks we realized that vampires were not

much of a threat. Let’s face it, vamps were dangerous for a while but in the third act they seemed to always trip on their capes and fall chest-first onto inconvenient pieces of sharpened wood. Or they’d get fried by sunlight after having failed to properly sun-proof their castles. Werewolves were only cranky three days out of the month, and I had four sisters, so I felt I was prepared. As far as mummies went, the ones in the flicks back then tended to shuffle along while wearing highly combustible old bandages, and, hell, we liked to play with matches.

On the whole, Jim and I figured we could handle just about anything that came our way. So we snuck in, bringing bottles of Hires root beer and paper bags of Night ’n Day licorice candy. The Midway used to be a vaudeville theater way back when, but most of it was falling down. The balcony had been officially condemned ten years before and was roped off. Which made it a moral imperative for us to spook our way up there and watch movies.

So there we were, two hardened street kids who had the whole thing figured out. We were ready for absolutely anything that could crawl, flap, fly, slither, or shamble across the silver screen.

Except that we weren’t.

No one who saw Night of the Living Dead without prior warning was ready. Not in 1968. No sir. Anyone who came to zombie flicks later—or to the genre through comics or TV shows—may appreciate and even love the genre, but unless they saw that movie on original release, they just don’t know how it felt.

No vampires. No werewolves. No mummies, creatures, demons, radioactive lizards, giant ants, or hideous sun demons.

Throughout most of the film we didn’t know exactly what these things were. That they were walking corpses we understood. That they ate people was obvious. But the why of it wasn’t made clear. Vampire and werewolf films carried with them a front-loaded mythology. Mummies were raised by spells and powered by tana leaves. King Kong lived on an island forgotten by time. Ghosts were dead people in danger of being cited for loitering.

But the living dead did not come with prehistory and no one in the film offered a definitive explanation. Scientists and the military speculated and contradicted each other. There was no Gene Barry or Edmund Gwenn to posit theories. Nor was there a Kenneth Tobey or Peter Cushing to dash heroically to the rescue.

The monsters were mysterious. They were enigmatic (a word I didn’t know back then). That was part of what made them so damn scary. No one in the story knew what was going on, and they never found out. I couldn’t remember seeing a single other movie where the entire cast of characters was clueless and, as a result, helpless because they had no information with which to form a plan.

Sure, there were rules, and I was on the edge of my seat watching as they figured out how to kill the living dead. But they didn’t know how the plague spread, and I started to get mighty darn nervous about the kid in the cellar with an infected bite. Surely that was going to be a bad thing. Right?

Right.

So, how did that film affect two hardened street kids?

It scared the bejeezus out of both of us. Not a joke and probably an understatement.

Jim chickened out and split right at the point where the young couple gets fried at the gas pump and becomes a hot buffet for the dead. He had issues with nightmares and bed-wetting for years. Not joking.

Me?

I stayed to see the movie twice.

And I snuck in the next day. And the next. Jim thought I was deranged. He thought I was sick in the head. Maybe I was. Or am. Same planet, different worlds.

I loved that movie. Still do.

That film became the first midnight movie in Philly. By the time I was fifteen it was the flick they showed at Halloween. You’d take a girl and she’d scream and bury her face against your chest and you’d offer comfort and that’s the birds and the bees, campers. At least in the late sixties and early seventies.

Night of the Living Dead became legendary. To be cool you had to see the movie, ideally at night, ideally at a drive-in or one of the old theaters. The Midway continued to play it every October, and then later it was picked up by some of the movie houses in Center City Philly. Then at drive-ins.

But none of us really knew what the monsters were.

The word “zombie” was never spoken in that movie, and George Romero was both surprised and annoyed when it was later attached to his films and then became the name for a new genre. He hadn’t made a zombie film. He’d made a ghoul film. He’d made a flick about flesh-eating corpses. Zombies were, to him and most of us back then, magically reanimated slaves in old movies from the thirties and forties set in Haiti. I Walked with a Zombie, White Zombie, and similar films were not the same genre as Night of the Living Dead. Not then and not now. Sure, some writers, historians, and critics have tried to make the connection with Romero and post-Romero living dead and the zombies of voodoo/vodun, but it’s a stretch. The Mummy has more in common with Haitian zombies than Romero’s ghouls, but that’s not a fight you can win.

As far as the entire fucking world is concerned, Romero invented the zombie genre.

What alarms and saddens me is when I meet people at book signings or conventions and they don’t know who Romero is. Not many, thank God, but enough to make me want to start biting people. Some of them seem to think zombies started with Max Brooks’s The Zombie Survival Guide or World War Z. Others think that the genre started with Marvel’s Marvel Zombies. And a lot are of the opinion that it started with Robert Kirkman’s The Walking Dead.

Here’s the thing. I’m friends with Max and Robert and I was one of the writers on Marvel Zombies Return. We’ve all talked about the genre and all of us agree that George Romero is the godfather. We wouldn’t have the careers we have had it not been for Night of the Living Dead. Not in any version of reality. That’s not to say that Max and Robert and the other top creators in the genre wouldn’t have become successful had they written any other kinds of stories, but we’re all clear on the debt we owe to George and his landmark film. And that goes for Shaun of the Dead, Resident Evil, Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, Z Nation, Left 4 Dead, Dead Set, iZombie, and … well, I could go on and on, because this genre is massive, and there’s nowhere on earth you can go where they don’t know what a zombie is.

And we owe big thanks to John Russo, who cowrote the script with George, and then went on to create a new generation of zombies in Return of the Living Dead. And to the cast and crew of Night of the Living Dead. They’re all demigods in the pantheon on the living dead.

The zombie (and, yes, we’re going to call it that now) was the scariest monster I’d ever seen. At ten years old they were also the most fascinating I’d encountered in books, comics, movie houses, or late-night TV. Walking home (alone) that first night I was already trying to work out how I would survive in that kind of scenario. Even now, I tend to check any building I visit in terms of defensibility, ingress, and egress. Like that. It’s a habit, and I’m reasonably sure I have reliable escape and survival plans worked out.

I wanted more of these monsters. There were some truly appalling knockoff movies in the years after Night but nothing that really captured the same feel. Then in 1978 George Romero released Dawn of the Dead. Not a sequel per se. More like another chapter in the same story. New locations, new characters, same problem. It was a corker of a flick and hits a lot of Best Of lists for enthusiasts of the genre and of horror films in general.

The Midway Theater—which was really crumbling by then—showed it on a double bill with Night. Yowzah.

For the record, my buddy Jim did not accept my invitation to go see it. He told me to go pound sand up my ass. Ah well.

In ’85, Romero hit us with a third film, Day of the Dead. And by now the genre was in full swing, at least in film.

There wasn’t much in the way of zombie literature, though. Some comics here and there, a few short stories, but nothing with real punch and not much of enduring quality. So, enter John Skipp. Writer, filmmaker, outside-the-box thinker, Skipp and his colleague Craig Spector were in dis

cussions with Romero about a possible film adaptation of their vampire novel. But Skipp decided to hit Romero with a crazy idea. How about an anthology of original living dead stories? Romero was skeptical that any such project would fly and famously offered to eat his hat if it was a success. Skipp and Spector reached out to the top guns of the horror biz and asked them if they’d like to do stories set in the world of Night of the Living Dead. Turns out a lot of the horror crowd had grown up with that flick, too. So in 1989, Skipp and Spector released Book of the Dead, with original stories by Stephen King, Richard Laymon, David J. Schow, Ramsey Campbell, Steve Rasnic Tem, Les Daniels, Douglas E. Winter, Joe R. Lansdale, Robert R. McCammon, and other gunslingers.

And that is where zombie literature was born.

The book was a huge hit, and the writers took the subject matter seriously, each bringing their A-game. I read that book until it fell apart and then bought a new copy. I love that book, and its sequel.

Since then I have read a lot of zombie lit.

I even took a few stabs at it myself. First with a nonfiction exploration of how the real world might react if Night of the Living Dead actually happened. My book, Zombie CSU: The Forensics of the Living Dead (Citadel Press, 2008), included interviews with hundreds of experts in law enforcement, medicine, science, and other fields, and it was no surprise to me that each and every person I talked to, no matter what their field, had already considered zombies and how they would relate to what they do. That was as true of forensic odontologists (bite mark experts) as it was of EMTs, SWAT team members, the clergy, the press, and … well … everyone.

Mostly, though, I’ve concentrated on fiction, and about a fifth of everything I’ve done deals with zombies, including two of my Joe Ledger thrillers (Patient Zero and Code Zero), a duology of mainstream horror novels (Dead of Night and Fall of Night), a steampunk novel based on a tabletop role-playing game (Ghostwalkers), comics (Marvel Zombies Return, Marvel Universe vs. the Punisher, Marvel Universe vs. Wolverine, and Marvel Universe vs. The Avengers), teen postapocalyptic adventures (Rot & Ruin, Dust & Decay, Flesh & Bone, Fire & Ash, and Bits & Pieces), and a slew of short stories and novellas.

Flesh & Bone

Flesh & Bone The Adventure of the Greenbriar Ghost

The Adventure of the Greenbriar Ghost Whistling Past the Graveyard

Whistling Past the Graveyard Scary Out There

Scary Out There The Wolfman

The Wolfman The King of Plagues

The King of Plagues Doctor Nine

Doctor Nine Fire & Ash

Fire & Ash The Dragon Factory

The Dragon Factory Deadlands: Ghostwalkers

Deadlands: Ghostwalkers Glimpse

Glimpse Mars One

Mars One Benny Imura 03.5: Tooth & Nail

Benny Imura 03.5: Tooth & Nail Bits & Pieces

Bits & Pieces Dust & Decay

Dust & Decay Patient Zero

Patient Zero The Orphan Army

The Orphan Army Ghost Road Blues

Ghost Road Blues Vault of Shadows

Vault of Shadows Dust and Decay

Dust and Decay Rot and Ruin

Rot and Ruin Code Zero

Code Zero Kill Switch

Kill Switch Like Part of the Family

Like Part of the Family Flesh and Bone

Flesh and Bone Bad Moon Rising

Bad Moon Rising V-Wars

V-Wars Dead & Gone

Dead & Gone Fire and Ash

Fire and Ash Hellhole

Hellhole Countdown

Countdown Dogs of War

Dogs of War Pegleg and Paddy Save the World

Pegleg and Paddy Save the World Dead Mans Song

Dead Mans Song Assassin's Code

Assassin's Code Dead of Night

Dead of Night Zombie CSU

Zombie CSU Dark of Night - Flesh and Fire

Dark of Night - Flesh and Fire Aliens: Bug Hunt

Aliens: Bug Hunt Broken Lands

Broken Lands Fall of Night

Fall of Night Ink

Ink Still of Night

Still of Night Relentless

Relentless Joe Ledger 1.20 - Story to the Dragon Factory - Deep, Dark (a joe ledger novel)

Joe Ledger 1.20 - Story to the Dragon Factory - Deep, Dark (a joe ledger novel) Property Condemned (pine deep)

Property Condemned (pine deep) The Dragon Factory jl-2

The Dragon Factory jl-2 Deep Silence

Deep Silence Joe Ledger

Joe Ledger SNAFU: An Anthology of Military Horror

SNAFU: An Anthology of Military Horror Assassin's code jl-4

Assassin's code jl-4 Code Zero: A Joe Ledger Novel

Code Zero: A Joe Ledger Novel Fire & Ash bi-4

Fire & Ash bi-4 Tooth & Nail (benny imura)

Tooth & Nail (benny imura) Dead Man's Song pd-2

Dead Man's Song pd-2 Joe Ledger: Unstoppable

Joe Ledger: Unstoppable The King of Plagues jl-3

The King of Plagues jl-3 The X-Files Origins--Devil's Advocate

The X-Files Origins--Devil's Advocate Limbus, Inc., Book III

Limbus, Inc., Book III Ghost Road Blues pd-1

Ghost Road Blues pd-1 Patient Zero jl-1

Patient Zero jl-1 Death, Be Not Proud

Death, Be Not Proud Countdown: A Joe Ledger Prequel Short Story to Patient Zero (joe ledger)

Countdown: A Joe Ledger Prequel Short Story to Patient Zero (joe ledger) Aliens

Aliens Extinction Machine jl-5

Extinction Machine jl-5 Ghostwalkers

Ghostwalkers Flesh & Bone bi-3

Flesh & Bone bi-3 Joe Ledger 2.10 - Material Witness (a joe ledger novel)

Joe Ledger 2.10 - Material Witness (a joe ledger novel) Nights of the Living Dead

Nights of the Living Dead Dead & Gone (benny imura)

Dead & Gone (benny imura) SNAFU: Heroes: An Anthology of Military Horror

SNAFU: Heroes: An Anthology of Military Horror Tooth & Nail: A Rot & Ruin Story

Tooth & Nail: A Rot & Ruin Story