- Home

- Jonathan Maberry

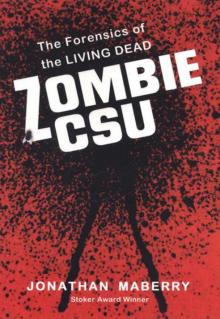

Zombie CSU Page 10

Zombie CSU Read online

Page 10

“An interesting point is whether or not zombies perspire,” says Leadbetter. “It they do, then it would be quite feasible that they would be able to leave fingerprints. Should it be that they do not perspire, then they would always be capable of leaving fingerprints in soft substrates such as chocolate, excrement, blood or toothpaste for example provided that the fingerprint detail did not break down before they joined the zomboid world. It would be interesting to note here, that due to the awkwardly articulated gait of the average zombie, the quality of fingerprint deposited by them would doubtless be subject to smudging and excessive distortion.”

JUST THE FACTS

DNA Testing

There are two primary kinds of forensic DNA testing: RFLP and PCR. RFLP (restriction fragment length polymorphism), is the more accurate of the two and is often called “DNA fingerprinting” or “profiling” and this involves the examination of sequences of base pairs in a section of a DNA strand. Since each DNA strand is unique, the identifiers in two samples will either match up (indicating they came from the same source) or they won’t, hence the reference to “fingerprinting,” which also matches specific patterns believed to be unique in each person. Though this is a very accurate test, RFLP has a downside in that it requires a fair amount of collected sample cells, such as large spatters of blood or several strands of hair. These samples also have to be fresh, undamaged, and only recently dead. The other downside to RFLP testing is the time involved: which is anywhere from two weeks to three months.

The PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test is less accurate, but police can get an answer in as little as a few days; this DNA does not have to be recently collected or fresh.

Expert Witness

“DNA testing has done a lot of good for the legal system,” says Georgia Stanley, a DNA testing technician for an independent New Jersey testing firm. “Not only is it contributing to the arrest of more criminals—and with a higher degree of certainty that they are the actual perpetrator; it is also helping to free persons wrongly convicted of crimes. Naturally courts would prefer the RFLP results because of their much higher degree of mathematical accuracy, but on the level of police work the less accurate but much faster PCR is very often used. The advantage there is that police can often identify a lead suspect and focus their investigation. Later, more elaborate testing may be ordered by either prosecution or defense.”

Donna Sims, another technician at the same firm, explains the range of DNA testing. “We get all kinds of test requests, not just crime. Over the last eight years that I’ve been here I’ve done testing to identify suspects based on DNA found at a crime scene; to identify plane crash victims; to identify animals on the endangered lists in the Jersey Pine Barrens; to exonerate people wrongly jailed for crimes they didn’t commit; to verify blood relations as part of an estate settlement; and to match organ donors and recipients.”

The Zombie Factor

The zombies in a more advanced state of decomposition would be less likely to leave behind identifiable prints, but DNA touch evidence would still be useful. Examining its DNA through computer sequencing can identify any type of organism. Identifying unique individuals within each species is a bit less precise, but nowadays human DNA samples can be matched to the level of mathematical certainty. DNA testing may not be much help in the first hours of a manhunt, but once the zombie has been captured or killed, its DNA can provide information to investigators that will help them identify the person the zombie formerly was and then backtrack his movements, hopefully to the source of the contamination.

In the longer run, scientists and doctors will examine the zombie DNA in order to understand the nature of the disease and/or mutation that created this flesh-hungry monster.

JUST THE FACTS

Bloodstain Pattern Analysis

Violence happens, blood spills. Bloodstain pattern analysis (BPA) is a hot topic in forensic science. Blood spatter10 is crucial evidence in many cases in that it can often help police positively ID victims and assailants. Advancements in DNA analysis have given this aspect of forensics a major boost, and along with blood typing and other tests, it provides law enforcement and the courts with potent weapons for apprehension and conviction.

BPA is the science of examining the distribution, locations, and shapes of bloodstains at a crime scene. Properly done it allows the expert to accurately determine the sequence of events during the commission of a violent crime.

This field encompasses many other areas of science and medicine, including biology, chemistry, math, physics, anatomy, and others.

The blood spatter expert has a complicated job and will attempt to:

Locate all individual stains and patterns.

Calculate the angle of impact for each stain in order to determine the direction from which the blood was traveling. (Remember, a bloodstain may be present when the victim and/or assailant is not.)

Describe each through notes, photos, and other recording methods.

Determine the approximate number of blows.

Determine the likely sequence of events.

Determine the mechanism that created each stain. Blood from a torn artery will be different from blood spray from a baseball bat to the head.

Determine the number of people present at the scene during the attack.

Determine the position of the victim and/or assailants during the attack. This takes into account any objects on the scene that a person may have encountered, touched, collided with, etc.; and objects that might have altered or interfered with the trajectory of blood.

Determine the probable weapon used in the attack (knife, gun, teeth…)

Determine the source of each bloodstain.

Locate wounds on the victim and/or assailant that correspond with spatters.

On average there is about 4 to 611 liters of blood in the human body, which accounts for approximately 8 percent of total body weight. A blood loss of 40 percent or more of the total volume will produce irreversible shock and death. This includes loss from external wounds and internal bleeding. Losing 1.5 liters will usually incapacitate most adults.

There are three categories for bloodstains:

Passive: These are bloodstains caused by gravity, as with blood dripping from a wound. They are categorized as clots drips, drops, patterns, and pools.

Projected: These are bloodstains from any exposed blood source that is under some pressure, such as an open artery; or wounds that are subjected to an action or force greater than the pull of gravity. This includes gushing blood, arterial spurts, cast-off stains (from someone shaking blood from their hands or weapon, etc.); and impact spatters. Each of these can be further broken down into subcategories of low, medium, and high velocity.

Transfer: These are created when a wet, bloody surface (such as a blood-smeared hand) makes contact with another surface (such as a wall). Transfer bloodstains include bloody footprints, contact bleeding, swipes, smears, wipes, and smudges.

Expert Witness

I asked Consulting Forensic Scientist George Schiro to comment on whether the type of weapon used in a crime can be deduced from blood spatter evidence. He said, “The only way that a type of weapon can be deduced from the bloodstain patterns is if there is a bloody impression of the weapon at the scene or if there is a void (a bloodless area) in the shape of a weapon on a bloodied surface. Blood spatter can sometimes indicate the nature of the injuries received. This can also be indicative of the type of weapon used. For example, a misting, fine spray of blood spatter might indicate a gunshot wound. Larger drops with directionality might indicate blunt force trauma or a stabbing. The bloodstain pattern analyst must be very cautious in attempting to determine the type of weapon based solely on blood spatter. Other information, such as an autopsy report, must be taken into consideration.”

I asked Schiro to comment on how temperature and other variables affect the collection of BPA: “A timetable for blood changes after spattering would be very difficult to determine. The changes depen

d on numerous factors including, but not limited to the individual’s physiology, the humidity, the temperature, wind speed, the absorbance of the surface, the surface texture, and the volume of blood deposited. In most cases, a small volume of blood will typically dry within several hours. The blood dries from the outside in and changes from red to a reddish brown color as it dries. Over time, large volumes of blood can also undergo serum and blood cell separation as the blood clots and dries.”

Since the responding officers in our research center scenario could not be sure if the bloodstains at the scene belonged just to the victim or to the attacker as well, I asked Schiro to comment on that. “Each individual stain isn’t necessarily documented in every case. The overall patterns can be documented using dictated or written notes and video. Photography is the primary tool for recording overall patterns and individual stains. Measurements in photographs may also be necessary when trying to determine the location of origin of a bloodstain. Sketches are also useful in demonstrating potential origins of bloodstains within a scene.”

If a biting attack were suspected, however, Schiro says that would make a difference: “The type of bloodstain patterns left by someone who savagely bit the victim depends on the location and severity of the bites. There would definitely be drip patterns. There may also be spurt patterns if arteries or lower leg veins are breached. If there was also savage clawing at the victim, then spatters showing directionality may be present at the scene.”

He then commented on the directionality of blood spatter evidence, which provides crucial evidence to the investigators: “Directionality of a bloodstain is determined by the shape of the bloodstain and sometimes the wave cast-off associated with bloodstain. Bloodstains striking a smooth surface at 90 degrees perpendicular to the surface typically leave a circular stain. The greater the angle, the more elongated and ovoid shape the stain becomes. Based on these shapes, the angle that the blood drop struck the surface can be estimated. If the stain has a wave cast-off or tail, then an imaginary arrow can be drawn originating at the wave cast-off through the most elongated part of the stain to indicate the location of the bloodstain’s origin. An arrow in the opposite direction shows the directionality of the bloodstain.”

The Zombie Factor

One thing none of the experts could agree on is whether zombies would bleed. Certainly in the Romero films zombies bleed…sometimes. When shot, most of them just take the wounds without dripping blood, while at other times they bleed quite freely.

One scene, in Dawn of the Dead, even made a good solid argument for zombies having a very active circulatory system. One of the two SWAT officers, Roger, was attacked in the shopping mall’s department store and was tackled to the floor. In the struggle he drove a screwdriver into the zombie’s ear, which then welled with bright blood. Blood wells only when there is blood pressure, and there is blood pressure only when the heart is beating.

This scene was echoed in the 2005 remake of Dawn of the Dead, when the character of Michael used the broken handle of a croquet mallet to impale a zombie’s head. Blood poured downward. Okay, so you could make a case that in the remake the blood was pouring downward, which only proves gravity not blood pressure; but a lot of the zombies bled in that film. And in all the zombie films. Just not all the zombies.

So, would zombies still have blood in their veins, pumping or not? If the skin was intact and a zombie got up, the blood should settle into the legs, which would look bloated and squashy. Forensic expert Schiro observes, “Typically, body position and gravity will dictate where the majority of blood will be found. Livor mortis or lividity occurs when the blood stops circulating and gravity causes the blood to pool in the lower areas of the body. If someone dies while lying on their back, then the blood will pool in the capillaries on the back. If they are reanimated and upright within about eight hours, then gravity will cause the blood to pool in the legs and arms. If they are reanimated after about eight hours, then the blood will become ‘fixed’ and remain stationary in the back.”

Another theory, supported by yet another special effect in the zombie films is that the blood thickens in the veins. How likely is that? George Schiro says that it’s not very likely. “Decomposing blood would not typically be thickened unless other decomposing elements were present. Decomposing blood actually tends to be thinner due to hemolysis—the breaking down of the blood components. The blood also takes on a bad smell and it goes from red to a greenish brown over time. Thinner blood would tend to act more like spattered water. Transfer stains would also be less distinct and more diffuse. Spattered stains would also tend to run more and not keep their original shape. Thickened blood would be more congealed and hold its shape longer in transferred stains. In either case, due to the altered properties of the blood, experiments would have to be conducted, just as they were in the early days of bloodstain pattern analysis, to determine the flight characteristics of decomposed or decomposing blood. Without this data, proper interpretation of living dead bloodstain patterns is not possible.”

And what would happen if anomalous blood was recovered at a crime scene? “If this type of blood was recovered at a crime scene, it would initially be perplexing and perhaps indicate that someone was using putrefied blood from a dead person to stage a crime scene,” Schiro insists. “As more incidents of its recovery occurred, then a pattern would be noted and it would be apparent that the dead were walking the earth and attacking the living.”

* * *

Blood Spatter Evidence by Jonathan Maberry

“If (anomalous) blood was recovered at a crime scene, it would initially be perplexing and perhaps indicate that someone was using putrefied blood from a dead person to stage a crime scene”—GEORGE SCHIRO, consulting forensic scientist

* * *

Our research center guard took a couple of shots at his attacker. Would there be any blood spatter from a walking corpse? Schiro believes so. “There would be blood spatter from a walking corpse, but only certain types of patterns would probably be present. For example, spurt patterns require circulating blood and expirated blood requires a cough reflex, so these types of patterns may not be present. Other bloodstain patterns may be found at a crime scene. The same trajectory process would hold true for zombies. Typically a BPA specialist is used to interpret the evidence. A crime scene investigator would be the one who documents and collects the blood, although a BPA specialist could also document and recover this evidence.”

What about blood tissue collected from a zombie crime scene? Would it be bloodless and therefore more anomalous? “I wouldn’t necessarily expect the tissue to be bloodless,” Schiro speculates, “although I would expect the tissue to be in a state of decomposition. The expert would collect the evidence and perhaps examine it him-or herself. Because of its nature, the tissue samples would probably be sent to a forensic pathologist for further evaluation. Initially it may be thought that someone is using decomposing remains to stage a crime scene. As more information becomes available, then only one conclusion would be possible: zombies are attacking the living.”

At which point the matter would go to SWAT or even higher up. Certainly the Centers for Disease Control would be contacted, and maybe even the World Health Organization. It’s not even inconceivable that the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) would be brought in, especially if there was some fear that zombies were the result of some kind of biological attack with a weaponized pathogen.

Michael Sicilia of California’s Office of Homeland Security (the state division of Homeland) comments, “OHS is different from DHS in that we are the State Homeland Security folks, a focus on California issues, and send the federal money to the locals. For this purpose, I’ll refer to DHS. Advances have been made in detection of anthrax, plague, and other bio-threats and there has been a lot of new technology deployed that can detect minute amounts of trace bio-threats in the environments. Some of these are mobile, and can be deployed to mass gatherings like the Superbowl; some are in city streets. In C

alifornia there are four regional threat assessment centers that mirror the FBI districts in the State. They are staffed with local police, fire, hazmat and public health professionals as well as FBI and DHS.”

When asked how DHS/OHS might get involved with a health crisis, Sicilia says, “As to when we would become involved, that depends on the nature of the event. There would need to be criminal intent that the attack was designed to cause terror to forward a political agenda, i.e., causing panic that would allow zombies to take over. OHS wouldn’t get involved otherwise.”

OHS/DHS would not, he tells us, just come in and take over as is often seen in movies. “Public Health officers would take the lead. If criminal activity were suspected, then the OHS would confer with the CDC on the federal level, and local public health officers would be in the lead role, because they have credibility with the public.”

But first let’s talk about those inconsistancies in zombie physiology that we’ve just discussed. Zombie films and books tend to play fast and loose with their own mythology in a number of ways, and one of the biggest areas for literary license is whether zombies are truly animated corpses. If we stay strictly in the realm of “well, it’s just a story” then we don’t have to come up with any logic; but readers and moviegoers are less credulous than they have been in previous generations. We’ve become jaded because we’ve seen way too much implausible nonsense, and what we want is a damn good reason to suspend our disbelief. To be fair, it’s not asking a lot.

Flesh & Bone

Flesh & Bone The Adventure of the Greenbriar Ghost

The Adventure of the Greenbriar Ghost Whistling Past the Graveyard

Whistling Past the Graveyard Scary Out There

Scary Out There The Wolfman

The Wolfman The King of Plagues

The King of Plagues Doctor Nine

Doctor Nine Fire & Ash

Fire & Ash The Dragon Factory

The Dragon Factory Deadlands: Ghostwalkers

Deadlands: Ghostwalkers Glimpse

Glimpse Mars One

Mars One Benny Imura 03.5: Tooth & Nail

Benny Imura 03.5: Tooth & Nail Bits & Pieces

Bits & Pieces Dust & Decay

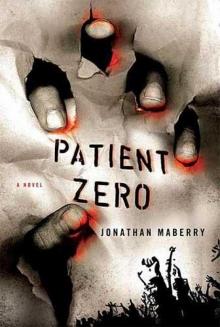

Dust & Decay Patient Zero

Patient Zero The Orphan Army

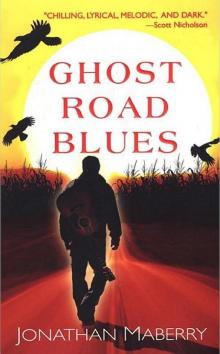

The Orphan Army Ghost Road Blues

Ghost Road Blues Vault of Shadows

Vault of Shadows Dust and Decay

Dust and Decay Rot and Ruin

Rot and Ruin Code Zero

Code Zero Kill Switch

Kill Switch Like Part of the Family

Like Part of the Family Flesh and Bone

Flesh and Bone Bad Moon Rising

Bad Moon Rising V-Wars

V-Wars Dead & Gone

Dead & Gone Fire and Ash

Fire and Ash Hellhole

Hellhole Countdown

Countdown Dogs of War

Dogs of War Pegleg and Paddy Save the World

Pegleg and Paddy Save the World Dead Mans Song

Dead Mans Song Assassin's Code

Assassin's Code Dead of Night

Dead of Night Zombie CSU

Zombie CSU Dark of Night - Flesh and Fire

Dark of Night - Flesh and Fire Aliens: Bug Hunt

Aliens: Bug Hunt Broken Lands

Broken Lands Fall of Night

Fall of Night Ink

Ink Still of Night

Still of Night Relentless

Relentless Joe Ledger 1.20 - Story to the Dragon Factory - Deep, Dark (a joe ledger novel)

Joe Ledger 1.20 - Story to the Dragon Factory - Deep, Dark (a joe ledger novel) Property Condemned (pine deep)

Property Condemned (pine deep) The Dragon Factory jl-2

The Dragon Factory jl-2 Deep Silence

Deep Silence Joe Ledger

Joe Ledger SNAFU: An Anthology of Military Horror

SNAFU: An Anthology of Military Horror Assassin's code jl-4

Assassin's code jl-4 Code Zero: A Joe Ledger Novel

Code Zero: A Joe Ledger Novel Fire & Ash bi-4

Fire & Ash bi-4 Tooth & Nail (benny imura)

Tooth & Nail (benny imura) Dead Man's Song pd-2

Dead Man's Song pd-2 Joe Ledger: Unstoppable

Joe Ledger: Unstoppable The King of Plagues jl-3

The King of Plagues jl-3 The X-Files Origins--Devil's Advocate

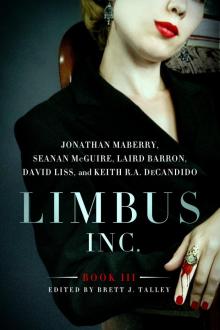

The X-Files Origins--Devil's Advocate Limbus, Inc., Book III

Limbus, Inc., Book III Ghost Road Blues pd-1

Ghost Road Blues pd-1 Patient Zero jl-1

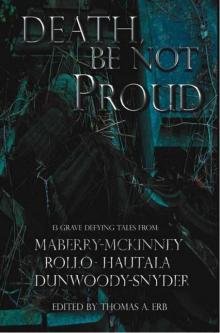

Patient Zero jl-1 Death, Be Not Proud

Death, Be Not Proud Countdown: A Joe Ledger Prequel Short Story to Patient Zero (joe ledger)

Countdown: A Joe Ledger Prequel Short Story to Patient Zero (joe ledger) Aliens

Aliens Extinction Machine jl-5

Extinction Machine jl-5 Ghostwalkers

Ghostwalkers Flesh & Bone bi-3

Flesh & Bone bi-3 Joe Ledger 2.10 - Material Witness (a joe ledger novel)

Joe Ledger 2.10 - Material Witness (a joe ledger novel) Nights of the Living Dead

Nights of the Living Dead Dead & Gone (benny imura)

Dead & Gone (benny imura) SNAFU: Heroes: An Anthology of Military Horror

SNAFU: Heroes: An Anthology of Military Horror Tooth & Nail: A Rot & Ruin Story

Tooth & Nail: A Rot & Ruin Story