- Home

- Jonathan Maberry

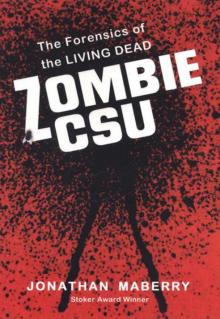

Zombie CSU Page 2

Zombie CSU Read online

Page 2

As I launched into my research, contacting cops, scientists, medical doctors, and forensics experts, I was delighted but not entirely surprised to find out that many of them had been thinking along the same lines. When I floated the question of how forensics would cope with the zombie threat, instead of getting doors slammed in my face, I got a wide welcome from men and women who, just like me, had sat in the dark as kids and watched zombie flicks and wondered…what if? Folks who, as professionals now in their fields, actually have some answers to those questions.

What if there were zombies? Could the routine and infrastructure of law enforcement and the combined strength of modern science be able to recognize and adequately respond to the threat?

You know…it just might.

Let’s go find out.

Reading This Book

So what if zombies existed? What if the very first zombie who rose from the dead killed someone? How would the police react? Would they be able to understand the nature of the crime…and the nature of the assailant? Would forensic evidence collection and medical science be able to discover the cause of the zombie plague? And, most important of all, would we be able to stop the wave of killing before a zombie apocalypse occurred?

In order to give us a framework on which we can build our case, we need to decide which kind of zombie attack is in question. The flesh-eating ghouls as shown in the majority of zombie films, and particularly in those of George A. Romero, will be our target. These are creatures that have been reanimated by some process currently unknown. In the Romero films there is an early theory that radiation from a returning space probe caused the rising. We’ll be discussing the likelihood of that, and also explore other theories that have been floated in zombie stories, particularly the idea of a virus. There are more zombie films and books with that as a basis than any other, and we’ll delve deep into the sciences of infectious disease and epidemiology. Since we’re in the realm of hard science here, we’re not only going to look at how collected evidence may help police track down the zombie and the source of the infection; we’ll also explore whether medical science can support the concept of a corpse that rises from the dead and attacks the living.

To explore the forensics of the living dead, we’ll construct a mock crime scene, taking it from the 911 call all the way to the attempt to apprehend the perpetrator. When you take a big picture view of a ghoul attacking and killing a person, you are really looking at a standard murder scene. There will be an incident, possibly witnesses to the event; police will respond in a certain way, following specific established and effective procedures; the scene will be secured and observed; evidence will be collected and processed; investigatory leads will be followed. Whether the perpetrator is Joe Ordinary, Jack the Ripper, or Bub the Zombie, a murder scene is a murder scene.

So let’s take it step by step.

But First a Word About Zombies

Images of the Living Dead by Jacob Parmentier.

“The first Zombie movie I ever saw was Night of the Living Dead and it was the original as well. I remember having dreams night after night of fighting off brain-sucking zombies for days afterward; but I think my true favorite of all the zombie movies would have to be The Evil Dead. I had a friend that had a VHS copy of this movie and I remember how taboo it was to have watched it.”

There’s an old adage popular among big-game hunters that goes: “Before you can hunt anything you have to understand it.”

That logic is so fundamental that it applies equally to wild animals, human enemies, or monsters from the grave.

Another variation on that thought is this one, roughly translated1 from the Hmong language of the Laotian mountain people, which observes: “If I know it then I can hunt it; if I do not know it then it can hunt me.”

So what are we talking about when we use the word zombie? What kind of monster are we hunting?

A GHOUL BY ANY OTHER NAME…

Zombie. The very word conjures disturbing images. Close your eyes and picture the living dead. You can see their pale, decaying faces; their vacant eyes sunk into dark pits; their slack and expressionless mouths. If you listen real hard, you can just about hear the slow, scuffling steps of a zombie as it shambles out of the shadows, tottering unsteadily as it approaches. You can hear the low moan that tells of a hunger so deep that it can never be satisfied. Take a whiff—that’s the smell of rotting flesh, the sickly sweet perfume of the open tomb.

But what are they? Historically zombie has meant different things to different people. To just about anyone born in the mid-to-early twentieth century (and yes, a lot of you are reading this, too), a zombie is a shambling living-dead person associated somehow—and you may not know exactly how—with the Haitian religion of voodoo. Those zombies are actually a real-world phenomenon…but are they the creatures we see in horror movies?

For an answer to that question, I asked one of the world’s great experts on the subject, Dr. Wade Davis, an ethnobotanist and author of a dozen books, including The Serpent and the Rainbow2 and Passage of Darkness. “Hollywood, and indeed much of the popular and political culture, has maintained a racist view of Haitian culture, vodoun,3 and zombies. American culture was demonstrably uncomfortable with the existence of Haiti—a nation whose slaves revolted and overthrew the white slave masters. The views of Haitian culture, whether written, spoken or filmed painted a picture totally at odds with the people and their beliefs. This propagandized view denigrates an entire religion.”

So then, what is a zombie?

“The zombie, by Haitian belief,” Dr. Davis explains, “is an individual who has lost their soul and been cast into purgatory. By that view the act of making a zombie is a magical act. The victims have lost their animus—their true personality—and their conscious control. In my books, Serpent and the Rainbow, and, more specifically, Passage of Darkness, I discuss how this is accomplished partly through what’s called ‘zombie powder,’ a concoction made from toad skin and the chemical tetrodotoxin,4 which is harvested from a species of puffer fish, which is the same order of fish as the Japanese fugu fish. The tetrodotoxin blocks sodium channels and lowers metabolic rates. A zombie of the vodoun kind is created in part by zombie powder and partly by the structure of the culture. Believing that becoming a zombie is possible helps to make it possible. It has a clear chemical base, but the creation of a zombie is a social event with spiritual, political, sociological basis.”

Are these zombies the same thing as the creatures that appear in modern horror films and in best-selling books like World War Z5 by Max Brooks?

* * *

Art of the Dead—Brian Orlowski

Drawn of the Dead

“Zombies have always scared me, much more than monsters or psychos or ghosts. Mainly because they start out as us. I think we are actually looking at our own reflection when faced with the undead. Your neighbors, family, spouse, they can all turn on you when you let your guard down and bad things happen. They are also so terrifying because they easily outnumber us. Whether it is the classic slow-moving corpse or the running, crazed ghoul, as quickly as you dispatch of one or two, ten more fall in to replace it. It’s the fear of a losing struggle, like fighting against quicksand. And the disease spreads from corpse to corpse, multiplying exponentially, until the Earth is rampant with the undead and we, as humans, have lost the fight. That is scary.

“However my art is predominantly humorous cartoons. So I use gore and violence for laughs. Whether it be queasy gross-outs or shock value gags, the reactions I get most are; ‘funny,’ ‘cool,’ ‘gross,’ and ‘you’re sick.’ And, yes, there’s social commentary built in as well.”

* * *

Dr. Davis is emphatic on this point. “No! The zombies in movies like Night of the Living Dead have no connection at all to the zombies of Haiti. It is not a correct or fair use of that word. Haitian zombies are not ghouls.”

Fair enough, but the word zombie is associated with another cultural phenomenon—and one that has had a mass

ive global impact. Unlike the creatures of Haiti, the zombies known to the general population are, in point of fact, flesh-eating ghouls. They are the recent dead, returned to a semblance of life, and their only apparent point for existing is to attack humans for food. They hunt and kill, hunt and kill, without rest, without sleep, without thought. And though it’s hard to admire savage cannibalism, one has to respect the degree of focus involved—it makes a person with OCD look fickle by comparison.

Technically our monster is a kind of ghoul…but even then we’re not being totally PC because ghoul also has an older and far different cultural connection related to desert demons variously known as the ghul and algul from pre-and-post Islam Arabic legend. Even here, though, the folkloric monsters had a number of different qualities that included intelligence (at times), cunning, and the ability to shape-shift.6

However, the Anglicized word ghoul has taken on a somewhat different and very specific meaning in Western culture: that of a dead creature that has risen from the grave to feast on human flesh. The movie version of this monster archetype—at least as defined in the earliest films of the genre—has no intelligence, no cunning at all, no ability to change shape, no qualities of any kind except an insatiable hunger and zero detectable brain function.7 The zombies in our pop-culture sensibility are actually mindless flesh-eating ghouls.

Zombie culture, as we know it today, really began in 1968 when George A. Romero, a young Pittsburgh industrial filmmaker, decided he was tired of doing the corporate stuff and wanted to try his hand at making a new kind of horror movie. His inspiration came neither from Haitian culture or Arab folklore, but drew instead on the neo-folklore of modern pop culture.

Mind you, these creatures weren’t actually called zombies until ten years after the whole “zombie craze” got started. That name became associated with it only after the sequel, Dawn of the Dead (1978), was released in the United States, and was then recut for European release by producer Dario Argento. He called it Zombi. Even then, the word is used very briefly in Dawn of the Dead (by the character Peter, played by an imposing Ken Foree), but it clearly wasn’t intended as a defining label at that point. With the European release the name stuck and here we are talking about zombies in the twenty-first century. And though this is on a par with calling all tissues Kleenex or all copiers Xerox it is the name that’s now hardwired into the consciousness of the mass popular culture. Zombie it became, and zombie, for good or ill, it will probably always be, I say this with genuine apologies to the people of Haiti and with respect to their cultural beliefs.

Besides, zombie is a handy, short, easily spelled, easy-to-remember label. After all, calling them reanimated flesh-eating corpses is a bit unwieldy.

ZOMBIE ROOTS

There are several classic movie genres and subgenres that have clearly influenced Romero’s work, but for the fabric of it, the material substance on which created what would become his own genre, he looked away from film and into fiction. He looked at Richard Matheson’s groundbreaking novel, I Am Legend, in which the author blended the vampire and science fiction genres into a single story that used science to ratchet up the fright.

Matheson’s story tells of a plague (bacillus vampiri) that sweeps the earth and turns everyone into vampires except one man. The book then explores the protagonist’s struggle to survive against an overwhelming army of the walking dead. I Am Legend, though a short novel by today’s standards, is dense with implied social and political commentary as well as insightful psychological subtext. This is a thinking person’s horror story, and arguably one of the most important books in the twentieth-century cannon of both science fiction and horror.

* * *

Art of the Dead—Mark McLaughlin

Advanced Decay

“Why did they come back to life? Who knows! A person can come up with any number of reasons—horrific, fantastical or science-fictional. Their flexible nature appeals to me, and so I use them in my artwork, and my fiction, too.”

* * *

In terms of film, the strongest obvious influence was Alfred Hitchcock’s 1963 film The Birds,8 one of the most significant entries in the “revenge of nature” subgenre in which a normal part of the natural world suddenly changes and becomes deliberately threatening. Hitchcock used birds, but the genre explored a lot of variations of this theme with decidedly mixed results. We had some exceptional entries beginning with an onslaught of giant ants in Them! (1954) and one really pissed-off shark in Jaws (1974); a few decent chillers like the rat-infested Willard (1971) and Ben (1972); a mixed bag of so-so flicks like the killer-whale gonna get you Orca (1977) and the weirdly wormy Squirm (1976); and some truly appalling pieces o’ crap like Night of the Lepus (1972), in which a southwestern town is attacked by flesh-eating killer bunnies (I’m not making this up!). In each of these films nature decides to stop being passive and takes a bite out of mankind. All great inspiration for George Romero.

The revenge of nature subgenre overlaps with “disaster films,” which typically pit a dwindling group of people against a natural (or in some cases man-made) catastrophe. Typical of the later zombie genre, it’s often the infighting among the struggling survivors that leads to their high mortality rate. Disaster films have been a staple of cinema since the industry’s earliest days, with early outstanding examples like Fire (1901), San Francisco (a 1936 earthquake movie), In Old Chicago (1937 story of that city’s great fire), and continuing on into the twenty-first century with The Day After Tomorrow (a global warming/new ice age cautionary tale inspired by the nonfiction book The Coming Global Superstorm by Whitley Strieber and Art Bell).

A fourth archetype that helped stir the pot for Night of the Living Dead was the apocalyptic thriller in which we see civilization as we know it crumble, often taking with it morality, compassion, and basic humanity. The novel I Am Legend also fits into this genre and has been adapted three times (so far) to films of this kind, beginning with The Last Man on Earth (1964) starring Vincent Price, The Omega Man (1971) with Charlton Heston, and most recently I Am Legend (2007) starring Will Smith. Oddly, both the Heston and Smith versions change the nature of the plague so that instead of vampires the bulk of humanity is transformed into mutated humans—though they did have an aversion to sunlight. As a purist and huge fan of Matheson’s original story, I disagree with this choice. Vampires are scarier than albino humans with sunglasses. Much, much scarier. At least with the Will Smith version, there was a fairly obvious attempt to riff off of the success of movies like 28 Days Later (2002) and its sequel 28 Weeks Later (2007), which used the zombie film model but with diseased humans rather than living dead.

28 Days Later is largely credited with rebuilding the zombie genre and, along with the comedy Shaun of the Dead (2004), bringing it to the moneymaking cinema mainstream. But without Night of the Living Dead there would have been no 28 Days Later; but without the book I Am Legend there almost certainly would never have been a Night of the Living Dead. So…Legend influenced Dead, which in turn influenced 28, which then influenced the newest film version of Legend. There’s something curiously inbred about all that, or is that just me?

THE ROMERO EFFECT

This was the pool from which Romero dipped to create the basis of his new horror film; but Romero was an innovator in his own right and wanted to tweak the model to fit his own dystopian vision and to carry his own brand of wry social commentary. He changed the vampires to flesh-eating ghouls and, instead of starting his tale after the fall of man, he chronicles the actual plummet by focusing on a small group of survivors holding out against an undead invasion.

Shot for pocket change ($114,000), Night of the Living Dead9 revolutionized horror forever, created a new monster paradigm, launched a lot of careers (actors, effects people, other directors, etc.), inspired many a sleepless night, and influenced film, TV, fiction, art, poetry, music, and even toys. The full impact of the “Romero Effect” cannot be calculated.

In his films, Romero does not make any direct refere

nce to religion or organic chemistry, and we’re always left wondering just how exactly these zombies came into being. In Night he suggests that a space probe (never seen and only obliquely mentioned) has returned to earth contaminated with an unknown form of radiation. Is this why the dead have risen? The talking heads seen on TV screens in some of the scenes float this as a theory, but no definitive statement is ever made. No attempt is made to explain the process, but the cause is less the point than how society reacts to this new threat. They rise, we fall…and one way or another it’s all our fault. Romero is not known for his enthusiastic optimism for humanity’s higher values.

In Dawn, Romero only lightly touches on religion and vodoun, and even then it’s clear this is not his message. The SWAT officer Peter (Ken Foree) makes the comment: “When there’s no more room in hell, the dead will walk the earth.” He says that it was one of his grandfather’s sayings, from Macumba, which is a Brazilian slang name for vodoun/voodoo based on the Bantu word for magic.10 The issue is not explored and is never mentioned again.

With the rise of the living dead, we suddenly have a new kind of horror storytelling. Instead of the thinking monster (vampires, demons), or the semi-intelligent but equally threatening supernatural beast (werewolves, mummies), or radioactive giants (Them!, Godzilla), we have something that borrows the best elements of each. We have a horde of nearly unstoppable, flesh-hungry dead who are, by their new nature, both fearless and relentless.

Flesh & Bone

Flesh & Bone The Adventure of the Greenbriar Ghost

The Adventure of the Greenbriar Ghost Whistling Past the Graveyard

Whistling Past the Graveyard Scary Out There

Scary Out There The Wolfman

The Wolfman The King of Plagues

The King of Plagues Doctor Nine

Doctor Nine Fire & Ash

Fire & Ash The Dragon Factory

The Dragon Factory Deadlands: Ghostwalkers

Deadlands: Ghostwalkers Glimpse

Glimpse Mars One

Mars One Benny Imura 03.5: Tooth & Nail

Benny Imura 03.5: Tooth & Nail Bits & Pieces

Bits & Pieces Dust & Decay

Dust & Decay Patient Zero

Patient Zero The Orphan Army

The Orphan Army Ghost Road Blues

Ghost Road Blues Vault of Shadows

Vault of Shadows Dust and Decay

Dust and Decay Rot and Ruin

Rot and Ruin Code Zero

Code Zero Kill Switch

Kill Switch Like Part of the Family

Like Part of the Family Flesh and Bone

Flesh and Bone Bad Moon Rising

Bad Moon Rising V-Wars

V-Wars Dead & Gone

Dead & Gone Fire and Ash

Fire and Ash Hellhole

Hellhole Countdown

Countdown Dogs of War

Dogs of War Pegleg and Paddy Save the World

Pegleg and Paddy Save the World Dead Mans Song

Dead Mans Song Assassin's Code

Assassin's Code Dead of Night

Dead of Night Zombie CSU

Zombie CSU Dark of Night - Flesh and Fire

Dark of Night - Flesh and Fire Aliens: Bug Hunt

Aliens: Bug Hunt Broken Lands

Broken Lands Fall of Night

Fall of Night Ink

Ink Still of Night

Still of Night Relentless

Relentless Joe Ledger 1.20 - Story to the Dragon Factory - Deep, Dark (a joe ledger novel)

Joe Ledger 1.20 - Story to the Dragon Factory - Deep, Dark (a joe ledger novel) Property Condemned (pine deep)

Property Condemned (pine deep) The Dragon Factory jl-2

The Dragon Factory jl-2 Deep Silence

Deep Silence Joe Ledger

Joe Ledger SNAFU: An Anthology of Military Horror

SNAFU: An Anthology of Military Horror Assassin's code jl-4

Assassin's code jl-4 Code Zero: A Joe Ledger Novel

Code Zero: A Joe Ledger Novel Fire & Ash bi-4

Fire & Ash bi-4 Tooth & Nail (benny imura)

Tooth & Nail (benny imura) Dead Man's Song pd-2

Dead Man's Song pd-2 Joe Ledger: Unstoppable

Joe Ledger: Unstoppable The King of Plagues jl-3

The King of Plagues jl-3 The X-Files Origins--Devil's Advocate

The X-Files Origins--Devil's Advocate Limbus, Inc., Book III

Limbus, Inc., Book III Ghost Road Blues pd-1

Ghost Road Blues pd-1 Patient Zero jl-1

Patient Zero jl-1 Death, Be Not Proud

Death, Be Not Proud Countdown: A Joe Ledger Prequel Short Story to Patient Zero (joe ledger)

Countdown: A Joe Ledger Prequel Short Story to Patient Zero (joe ledger) Aliens

Aliens Extinction Machine jl-5

Extinction Machine jl-5 Ghostwalkers

Ghostwalkers Flesh & Bone bi-3

Flesh & Bone bi-3 Joe Ledger 2.10 - Material Witness (a joe ledger novel)

Joe Ledger 2.10 - Material Witness (a joe ledger novel) Nights of the Living Dead

Nights of the Living Dead Dead & Gone (benny imura)

Dead & Gone (benny imura) SNAFU: Heroes: An Anthology of Military Horror

SNAFU: Heroes: An Anthology of Military Horror Tooth & Nail: A Rot & Ruin Story

Tooth & Nail: A Rot & Ruin Story