- Home

- Jonathan Maberry

SNAFU: An Anthology of Military Horror Page 6

SNAFU: An Anthology of Military Horror Read online

Page 6

Each time I expected to die and didn’t, I felt like I was cruising more and more on borrowed time. When it comes to counting the grace of God – or whoever else is on call for this little blue marble – I’m overdrawn at the bank. One of these days they’re going to foreclose on me, and I won’t have any luck or grace left to pay the bill.

I thought today was that day.

Today should have been.

Just as being a good person doesn’t give you any added protection, being a right bastard doesn’t necessarily guarantee that you’ll meet the fate you deserve.

The helicopter went down.

I didn’t.

Not entirely.

I woke upside down.

In a tree.

A long goddamn way from the ground.

Not the first time this has happened to me, either.

My life blows.

-3-

The first rule of survival is: Don’t panic.

Panic makes you stupid and stupid makes you dead.

Panic also denies you the opportunity to learn from the moment. You take a breath and judge the immediacy of your experience. You need to assess everything. Mind, body, equipment, environment… all of it.

The bright blue of the sunny sky had faded to a washed-out and uniform gray, so I had no way of telling the time. No way to judge how long I’d been out. Five minutes? Hours? I wasn’t hungry or thirsty enough for it to be longer than that. Our Black Hawk had been hit by something – probably a rocket-propelled grenade – at around ten in the morning.

My mind was fuzzy. That was the easy part to figure out. There was a big lumpy hot spot on the back of my skull where I’d hit something during the crash. My helmet was gone.

Most of the rest of my body felt sore and stretched, but hanging upside down will do that. Plus there would have to be some minor dents and dings from when I bailed out of the Black Hawk.

I paused, frowning.

Had I bailed out? I couldn’t remember doing that, though I must have because I wasn’t crumpled up inside the fallen bird.

Moving very, very carefully, I leaned back and looked down. The floor of the forest was about forty feet below me. Long damn drop.

Then I took a breath and tightened my stomach muscles to do a gut-buster of a sit-up. On good days I can bang out a whole bunch of these. Flat, on inclines, and clutching weights to my chest. Today was not a good day, so it took a whole lot of whatever energy I had left to lift my upper body high enough to see what was holding my feet in place.

I expected to see a tangle of branches. Or something from the chopper – rope, a cable, some of the net strapping used to secure cargo. I stared at my feet, at what held me to the tree.

No rope.

No cables.

Nothing that had been on the Black Hawk.

Nothing that belonged in this forest, either.

Nothing that belonged anywhere.

I was lashed to the branch by turn-upon-turn-upon-turn of glistening silk.

The strands were as thick as copper wire. And far stronger.

I turned and looked around at the rest of the tree. That’s when I saw it. It wasn’t that the day had become hazy and gray with clouds. No, there was more of the silk stretched in wild, haphazard patterns between the trunks and leaves.

All silk.

I wasn’t hanging from a tree.

I was caught in a web.

Yeah.

A fucking web.

-4-

It’s moments like this that make you want to seriously freak out.

I mean go total bug-eyed, slavering ape-shit nuts.

A spider web big enough to cover half a mile of treetops and hold a two-hundred-pound man – complete with combat gear – suspended? Yeah. Panic time. That is not normal, even for me. That is not something you start the day either psychologically- or tactically-prepared for.

Which changed the process.

Instead of letting calm passivity inform you and help you plan, you go bugfuck nuts and get the hell out of there.

Maybe you scream a little.

I did. Sue me.

I snaked out a hand and caught the thickest part of the branch I could, careful not to grab more of the webbing. Once I steadied myself, I reached into my right front pants pocket for my Wilson rapid-release knife. I wear it clipped to the lip of the pocket and it was still there. I pulled it free and flicked my wrist to snap the three-point-eight inch blade into place. That blade is short, but it’s also ultra-light and moves at the speed of my hand, which means it can move real damn fast.

I slashed at the web, terrified that the blade might stick or not be tough enough to slice through the fibers.

“Come on, God, cut me one frigging break here.”

The blade bit deep and the fibers parted.

I chopped and slashed and even stabbed at it, nicking my boots, slicing my trouser legs.

Suddenly I was free, and gravity jerked my feet straight down. My steadying grip on the branch immediately became the only thing preventing me from plunging down to a bone breaker of a landing.

I couldn’t close the blade one handed so I had to risk putting it into my pocket still open. Somewhere up in Valhalla I could see the gods of war raise their eyebrows and blow out their cheeks as if to say, “Boy’s tough but he’s a bit of an idiot.”

Whatever. I needed my other hand and I didn’t want to throw away the only weapon I had left. My rifle was probably in the chopper, and my holster was empty; the Beretta had probably fallen out while I hung upside down.

With a growl of effort and a lot of fear-injected adrenaline I swung sideways and up and caught the branch with my other hand. The bark was rough, but the wood was solid.

I hung there.

Boots swaying above the ground.

Streamers of spider web hanging around me.

What on earth had spun those webs? What on earth could have spun anything that big? The thought of some lumbering monster as big as a Range Rover scuttling toward me on eight massive legs was unbearable.

Was that what this was, or was my imagination taking the facts and spinning them out of control? Distorting them into science fiction implausibility. After all, there were spider colonies that made webs as massive as this. There were wasps and moths that covered trees with their nests.

That’s what this could be.

Not one big monster, but many small ordinary-sized ones.

It sounded good. It sounded great. It was doable. I could bear that.

Except that the strands hanging down around me were too thick. Too damn thick. No tiny insect body had spun them.

My mouth went totally dry.

Then I saw something that made it all much, much worse. Up there, tucked into the folds of the webbing, half-hidden by boughs of pine, were bones. I hung there and stared at them. I could see the distinctive knobbed end of a femur. In my trade you get to know the difference between animal and human bones.

The thing I was looking at was a human thighbone. Above it, obscured by shadows, were a half dozen curled and cracked ribs still anchored by tendon to the sternum.

Get out of here, I told myself.

I lingered a moment, though.

I listened to the trees, tried to hear past the soft rustle of branches stirred by leaves. Needing to hear any sounds that didn’t belong.

There was nothing.

Nothing.

And then…

Something.

Not close, but still too close. A scratching sound.

Like something climbing.

Then a brief, high-pitched cry. Not an animal cry, though. This was a chittery sound. Like a locust or a cicada.

Get the hell out of here right now.

My heart was hammering like mad, and sweat poured down my body. I had to get out of here right damn now.

I began climbing sideways, sliding one hand and then another to move along the branch. It was strong, but I was a solid two hundred pounds. The green wood c

reaked. And then there was a single gunshot-loud crack and suddenly I was moving downward. Not falling. Swinging. The branch broken but didn’t snap completely off. It swung me down like a lever and I thudded hard into the trunk and started to slide down. I instantly lunged for a second branch. It was smaller and broke right away, but it slowed my rate of fall. Not much, just enough for me to snake out a hand and catch another branch.

Which broke.

And another.

Which broke.

And that’s how I went down the tree. Each branch cracked and folded inward, slapping me over and over again into the trunk. Each time I cried out in pain, and each time I slid down the rough bark. I couldn’t hear the scratching sounds of whatever had made that nest, but no doubt it was coming. It was an awkward, painful, lumpy, uncertain process of fleeing by falling.

When I reached the lowest branch it held and I clung to it with desperate force, panting, praying, locking my fingers around it and holding on for dear life. When I built up the nerve, I looked down.

My boots were maybe six or seven inches from the green grass. I almost laughed, but instead I let go and thumped down onto the grass. My knees buckled and I dropped to them, then toppled sideways, my body feeling raw and beaten, my arms aching.

Above me the trees swayed and shadows seemed to curl and roil under the gray webbing.

I got back to my knees and carefully reached into my pocket for my folding knife. It was there, but as I drew it out I saw that it was the wrong color. Instead of bright silvery steel, I saw dark red smears.

That’s when I felt the warm lines running down the outside of my thigh. Very little pain, though. Or maybe so much pain elsewhere that I didn’t really feel it; but I knew that somewhere on my thigh was a cut. Couldn’t be too deep. I hoped. I had no first aid kit.

The trees above me rustled.

Get out of here, I told myself. You’re not bleeding to death, so get your ass in gear. Go anywhere but don’t stay here.

But that was as much bad advice as good. Fleeing was not really an option.

I tapped the earbud I wore, but there was only static. I figured that much. I quickly checked, and the little battery signal booster I wore was no longer in my pocket; until I could find it, I wasn’t going to be making any long distance calls. At best I might pick up chatter from anyone within a mile and on the same frequency.

I was in the Pacific Northwest, in the vast and seemingly endless forests of the Washington State timber country. All around me were millions of trees. Douglas fir, hemlock, ponderosa pine, white pine, spruce, larch, and cedar. The whole world was the green of pine needles and the dark brown of tree bark.

There had been four other people in that Black Hawk. There had been a briefcase filled with biological samples that I needed to get to my boss, Mr. Church, because he needed to get them into a goddamn vault where they would never see the light of day again. I was on my way back from a quick and dirty piece of business on the Canadian border where I’d helped dismantle a small but effective bioweapons lab. The bad guys were Serbians who had shanghaied a couple of biochemists and forced them to make designer bioweapons. Nasty stuff. Not doomsday plagues, but pathogens lethal enough to kill sixty percent of the crowd in Times Square on New Years Eve. That’s six hundred thousand potential victims.

I went in with two of my guys, Top and Bunny. My right and left hand. Top was First Sergeant Bradley Sims, a former Ranger who’d come out of retirement to fight in the Middle East war that had killed his only son and crippled his niece. He’d been recruited into the Department of Military Sciences because he was very probably the best special ops team leader in the business. Bunny was Staff Sergeant Harvey Rabbit, a six-and-a-half foot kid from Orange County. Looked like a surfer boy, fought like one of the Titans from Greek legend. Stronger than just about anyone you’re ever going to meet.

Top and Bunny.

They were out here. Somewhere.

Alive, I prayed.

Or dead, I feared.

The other three were the crew of the Black Hawk. I didn’t know them. They’d been sent to extract us when the Serbians went ass-wild on us and put forty guys in the woods with RPGs and LAW rockets. Our chopper had made maybe six of the eighty-two mile journey to the nearest populated town before it was brought down.

I needed to find my men. I needed to find that metal case filled with weaponized pathogens. A working radio would be pretty damn nice, too. So would a gun.

I froze. Above me I could hear the scratching sound.

Louder.

Closer.

I got to my feet and ran.

-5-

No, I don’t know what I was running from.

Maybe another guy – an ordinary chap or even a regular soldier – would have been stalled on that one thing. The giant web. And, sure, I was pretty freaked out about it. However I’m not an ordinary chap. I work for the Department of Military Sciences. We see the truly weird stuff that’s out there. Sure, most of the time that’s either a designer pathogen, a doomsday plague, transgenic manipulation, biotechnology like exoskeletons and cybernetic implants, nanites, or a dozen different madhouse attempts to cook up a super soldier. Frankenstein stuff. Jekyll and Hyde, if Jekyll worked for the government and Hyde was a field op. In the five years I’ve been rolling out with Echo Team and the DMS, I’ve seen horrors that stretch beyond anything I’d imagined was even potentially real before I’d joined. A prion-based plague that turned people into something too damn close to flesh-eating zombies. Genetically-engineered vampire assassins. Ethnic-specific diseases cooked up by modern day Nazi eugenicists.

Like that.

Giant spiders? Scary as shit, but if I could get me a good handgun or, better yet, a machine gun, I was going to ameliorate my terror by proving that armor-piercing rounds are an adequate answer to just about all of life’s little challenges.

The downside to that kind of bravado?

Yeah, I didn’t actually have a gun.

So, like any sane person who thinks there might be giant spiders in the trees, I ran away.

As fast as I could.

Then I skidded to a stop.

Far away and far downhill I heard the chatter of automatic gunfire. Heavy caliber rifles. AK47s, without a doubt. You go into combat on a regular basis you get to know the sounds of different kinds of guns.

Serbians.

Then I heard another sound. A long, ripping, soul-searing shriek of total pain. A human voice raised to the point of red inhumanity. It rose and rose and then was suddenly gone. Shut off. Torn away.

The sounds – gunfire and screams – had come rolling up the slope at me. Somewhere downland, bad things were happening. That was a direction I absolutely did not want to go.

But it was where I had to go.

God damn it.

I bent low, faded behind any available shrubs I could find, and ran toward the sound of battle and death.

-6-

There was a steep gully cut into the landscape and it provided shelter and an easier path downhill, so I slid down the side and jogged along the bottom. The ground here was moist and marshy and it was a good ten degrees colder. It was also much darker than I expected and soon I had to slow down and feel my way through sections that were black as night.

I fumbled my way around a bend in the gully when I smelled something burning.

Correction. Something burned. A past-tense smell.

Oil and copper wires and plastic. Meat, too.

I rounded the bend and there it was. Sprawled across the gully, its back broken, its skin black and blistered.

The helicopter.

The vanes were all gone. So was the tail section. The Black Hawk’s hull was crumpled from the impact with the ground, but I couldn’t see the kind of blast signature a rocket-propelled grenade should have made. And yet something had hit us hard enough to knock us out of the sky.

As I crept toward it I could see shapes inside. Twisted and withered from the heat.

Two of them. Both buckled into their pilot’s chairs.

Gone. Neither of them had ever had a chance. They’d stuck with it, fighting the controls of the dying chopper, and it had killed them down here in the moist darkness. Crushed them and cooked them.

Two men whose names I didn’t know. Part of an extraction team. Men I would probably have gotten to know once we were back in the world. We would’ve had beers, swapped lies. Become real people to one another.

Now they didn’t even look like people.

It took me three minutes to find the third man. What was left of him, anyway.

He lay against the steep slope of the gully forty yards beyond the smashed nose of the Black Hawk. His legs and face were burned, but it wasn’t fire that had killed him. When we’d boarded the chopper he’d taken possession of the metal suitcase in which the bioweapons were stored. Per our protocol, he’d sealed the case and then cuffed it to his own wrist.

The wrist and the cuff were still there.

The man’s hand lay on the ground between his feet. The case was gone.

The soldier’s body was riddled with so many bullets he was in shreds. Hundreds of shell casings lay in the damp earth. The Serbians had slaughtered him, a needlessly brutal demonstration of force to recover their bioweapon.

In the distance there was more gunfire.

They were still fighting. Their team had not been extracted and I had to wonder why. If they had the case, then why linger? Even if Top and Bunny were both out there, what use would it be for the Serbians to hunt them down? They’d won. All they had to do was leave and my guys would spend a couple of long, hard days walking out of these deep woods. By the time Top and Bunny reached a working phone, the Serbs would be back home, or they’d have vanished into a safe house.

Flesh & Bone

Flesh & Bone The Adventure of the Greenbriar Ghost

The Adventure of the Greenbriar Ghost Whistling Past the Graveyard

Whistling Past the Graveyard Scary Out There

Scary Out There The Wolfman

The Wolfman The King of Plagues

The King of Plagues Doctor Nine

Doctor Nine Fire & Ash

Fire & Ash The Dragon Factory

The Dragon Factory Deadlands: Ghostwalkers

Deadlands: Ghostwalkers Glimpse

Glimpse Mars One

Mars One Benny Imura 03.5: Tooth & Nail

Benny Imura 03.5: Tooth & Nail Bits & Pieces

Bits & Pieces Dust & Decay

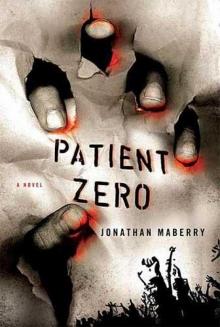

Dust & Decay Patient Zero

Patient Zero The Orphan Army

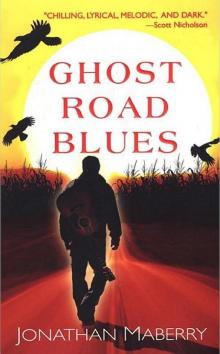

The Orphan Army Ghost Road Blues

Ghost Road Blues Vault of Shadows

Vault of Shadows Dust and Decay

Dust and Decay Rot and Ruin

Rot and Ruin Code Zero

Code Zero Kill Switch

Kill Switch Like Part of the Family

Like Part of the Family Flesh and Bone

Flesh and Bone Bad Moon Rising

Bad Moon Rising V-Wars

V-Wars Dead & Gone

Dead & Gone Fire and Ash

Fire and Ash Hellhole

Hellhole Countdown

Countdown Dogs of War

Dogs of War Pegleg and Paddy Save the World

Pegleg and Paddy Save the World Dead Mans Song

Dead Mans Song Assassin's Code

Assassin's Code Dead of Night

Dead of Night Zombie CSU

Zombie CSU Dark of Night - Flesh and Fire

Dark of Night - Flesh and Fire Aliens: Bug Hunt

Aliens: Bug Hunt Broken Lands

Broken Lands Fall of Night

Fall of Night Ink

Ink Still of Night

Still of Night Relentless

Relentless Joe Ledger 1.20 - Story to the Dragon Factory - Deep, Dark (a joe ledger novel)

Joe Ledger 1.20 - Story to the Dragon Factory - Deep, Dark (a joe ledger novel) Property Condemned (pine deep)

Property Condemned (pine deep) The Dragon Factory jl-2

The Dragon Factory jl-2 Deep Silence

Deep Silence Joe Ledger

Joe Ledger SNAFU: An Anthology of Military Horror

SNAFU: An Anthology of Military Horror Assassin's code jl-4

Assassin's code jl-4 Code Zero: A Joe Ledger Novel

Code Zero: A Joe Ledger Novel Fire & Ash bi-4

Fire & Ash bi-4 Tooth & Nail (benny imura)

Tooth & Nail (benny imura) Dead Man's Song pd-2

Dead Man's Song pd-2 Joe Ledger: Unstoppable

Joe Ledger: Unstoppable The King of Plagues jl-3

The King of Plagues jl-3 The X-Files Origins--Devil's Advocate

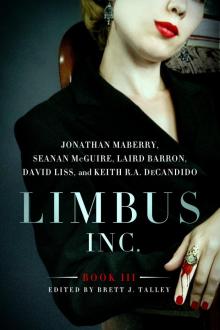

The X-Files Origins--Devil's Advocate Limbus, Inc., Book III

Limbus, Inc., Book III Ghost Road Blues pd-1

Ghost Road Blues pd-1 Patient Zero jl-1

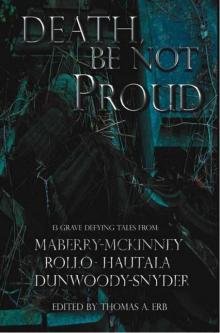

Patient Zero jl-1 Death, Be Not Proud

Death, Be Not Proud Countdown: A Joe Ledger Prequel Short Story to Patient Zero (joe ledger)

Countdown: A Joe Ledger Prequel Short Story to Patient Zero (joe ledger) Aliens

Aliens Extinction Machine jl-5

Extinction Machine jl-5 Ghostwalkers

Ghostwalkers Flesh & Bone bi-3

Flesh & Bone bi-3 Joe Ledger 2.10 - Material Witness (a joe ledger novel)

Joe Ledger 2.10 - Material Witness (a joe ledger novel) Nights of the Living Dead

Nights of the Living Dead Dead & Gone (benny imura)

Dead & Gone (benny imura) SNAFU: Heroes: An Anthology of Military Horror

SNAFU: Heroes: An Anthology of Military Horror Tooth & Nail: A Rot & Ruin Story

Tooth & Nail: A Rot & Ruin Story