- Home

- Jonathan Maberry

The King of Plagues jl-3 Page 7

The King of Plagues jl-3 Read online

Page 7

“Who’s training them?”

“Unknown.”

“Any of them in custody?”

“So far none have been taken alive.”

“Pity,” said Welles.

“Yeah,” I said. “We’re anxious to have a meaningful chat with one of them.”

“What else have you learned?”

“Not much. There’s someone called the Spaniard who acts as a liaison between the street teams and the Kings. He’s known to be utterly ruthless and to have a special love of torture with knives and edged weapons. But that’s all we have on him. Everyone we’ve heard of who has run afoul of him is dead. I saw one of his victims. Not a pretty sight.”

Aylrod said, “Any leads through the equipment they use?”

“No. It’s either Russian or Chinese made or stolen American stuff. The street teams are more likely to have AKs; the Kingsmen came at us with M4A1 carbines and a couple of HK416s. Those HKs are state-of-the-art-Delta Force weapons.”

Aylrod nodded gravely, then pointed to the screen. “What happened after the logo was painted?”

“He walked away,” said MacDonal. “The camera at the corner caught him, but then he vanished. Looks like he either entered the hospital or somehow slipped away out of sight of the other cameras. We have someone searching the camera feeds in an expanding grid to see if he shows up anywhere else.”

The Home Secretary nodded. “Assessment?”

MacDonal pursed her lips. It made her look like an evil librarian. “The person in the video may or may not have been part of this Seven Kings group. He could have been a gangbanger given a few quid to paint that on the wall.”

“That was a grown man,” Childe observed. “Not a teenager.”

“How can you tell?” asked Welles.

“General build and the way he walked. He was confident and careful, but not furtive.”

I nodded. “And he’s painted that logo before. He wasn’t tentative about it. He wasn’t trying to figure out what to write or how to write it. He did it as quickly and smoothly as if he’s done it plenty of times before.”

“A gangbanger would be just as quick and smooth,” MacDonal said.

“Sure,” I agreed, “but as Mr. Childe pointed out, this was no kid.”

Welles said, “Any clue as to why this group calls itself the ‘Seven Kings’?”

Benson Childe shook his head. “We helped the DMS with the research on that, but so far we haven’t struck gold. There are over three hundred thousand hits on that name on the Internet. A boat storage facility and a real estate developer of that name, both in Florida; the Seven Kings Relais hotel in Rome; a mystery novel called The Brotherhood of the Seven Kings published in 1899; a tomb of the Seven Kings in Andhra Pradesh, India; a punk rock band of that name; and even a town here in London.”

“Where in London?” asked Welles.

“It is a suburban development in the borough of Redbridge, part of the Ilford post town. We have people out there, but so far that image has not been found on any walls.”

“We’ll send this out to all stations and departments,” concluded Welles. “And I believe that we’ll be using Captain Ledger as an advisor. He’s asked to be part of the hospital investigation and I think that would be a wise choice. Moving on. What do we know about the actual fire?”

“The fire is still too hot for a proper analysis,” said a frail-looking man with watery brown eyes who sat next to Childe. Unlike the others, he hadn’t given me his card. “But from gasses collected at the site the fire investigators have verified the presence of nitrates, and in great quantities. This was definitely a bomb. Or, more precisely, several.”

“How many, Darius?” asked Welles, and that fast I knew who the frail man was. Darius Oswalt, Director General of MI5. I knew him by name and reputation, but the mousy physique didn’t match the legends I’d heard. I expected a Daniel Craig type, not someone who looked like a low-level chartered accountant.

Oswalt spread his hands. “We’ve looked at the CCTV feeds from the moments leading up to the explosion. Witness reports vary between four and nine blasts. However, we estimate that there were fourteen.”

“Fourteen?” gasped Welles.

“No one reported that,” said Aylrod.

“Not surprising,” said Oswalt. “But the CCTV images of Whitechapel Road show fire erupting from multiple points when the ‘first’ blast happened. We believe that all of the bombs had been set to detonate at the same time and were positioned to do the greatest possible structural damage. Considering how much of the complex has already collapsed, I think it’s a safe bet that many of the charges did, in fact, simultaneously detonate. As for the mistiming? There are always some x-factors when it comes to the wiring and setting of the digital timers. The blasts all happened within four seconds of each other, though, so it’s as close as may be. How the terrorists managed to smuggle fourteen bombs, give or take, into a building with moderately good security—well, that’s the real question, isn’t it?” He paused and from the look on his face it was clear that he had a bomb of his own to drop. “Based on the CCTV footage, we can make a pretty good guess as to the time the perpetrators intended all of the bombs to go off.”

“What time?” I asked, and everyone leaned forward, caught by Oswalt’s grave tone.

The MI5 man sucked his teeth for a moment, eyes introspective.

“According to CCTV,” he said slowly, “the bombs detonated at precisely eleven minutes after nine this morning.”

“Bloody hell,” murmured Aylrod.

I closed my eyes for a moment and felt an old ache in my chest.

The bombs had gone off at 9:11.

Interlude Five

The State Correctional Institution at Graterford

Graterford, Pennsylvania

December 17, 1:51 P.M. EST

He sat in his cell and smiled at the shadows. The cockroaches were his friends. The spiders, too, and he read great mathematical truths in the subtle intricacies of their webs.

The guards feared him. The gangbangers never messed with him. They’d tried during his first week, but never again. Longtime inmates gave him space in the mess hall and would walk out of their way so as not to step on his shadow during afternoon exercise. The multitude of the Aryan Brotherhood mythologized him, ascribing biblical powers to him and endlessly arguing over hidden meanings in his most casual comments. Men had been shanked over such disputes. The Jamaican and Haitian convicts thought that he was some kind of white bokor. The Muslims thought that he was a demon. The madmen among the prison population thought he was a god. Or an angel. Men had been killed for speaking ill of him.

In truth, Nicodemus took no sides among the thirty-five hundred prisoners within the walls of Pennsylvania’s largest maximum-security correctional facility. He would not allow himself to be tattooed with gang markings or colors. He did not deliberately sit with any one group or another. When asked why by a wide-eyed and fatuous young Latino fish, Nicodemus had closed his eyes and said, “Because I belong to all of His people.”

“Whose people? God’s? People say that you think you talk to God. Or maybe the Devil. But that’s just bullshit, isn’t it?”

Nicodemus merely smiled and did not answer. A week later Jesus Santiago was found dead in the laundry room. His tongue had been cut out and the numbers 12/17 were carved nine times into his flesh on his chest and back. The medical examiner concluded that Santiago had died from a heart attack. He was twenty-one years old and had no history of heart trouble.

Nicodemus told the prison psychiatrist that he knew nothing of the young man named Jesus Santiago. “No such person dwells within my mind,” he said. “I cannot see him with my left eye, nor do I see him with my right.”

“You were seen speaking with the boy,” prodded the psychiatrist, Dr. Stankeviius.

“No,” said Nicodemus. “I was not.”

“A guard saw you.”

“If he says so, then he is mistaken. Ask him again.

”

When the doctor asked Nicodemus if he knew the significance of the numbers 12/17, the little prisoner smiled. “Why ask a question to which you already know the answer?”

“I don’t know the answer, Nicodemus. Why don’t you tell me?”

“Time is not like a ribbon stretched from now until then. It is a pool in which we all float.”

“I don’t know what that means.”

“Search your mind. Dive into that pool.”

That was all that Nicodemus would say. His eyes lost their focus and he appeared to go into his own thoughts.

After the session was over, Dr. Stankeviius searched through the folder for the eyewitness report by the guard who had been walking the yard that day. The report was gone. The psychiatrist requested that the guard be brought into his office, but the officer in question had not reported for work that day. When Dr. Stankeviius pressed the matter, he learned that the guard had been transferred to a facility in Albion, at the extreme northwest corner of the state. No attempt to contact him either through the system or via personal telephone or e-mail was successful. Two weeks later the guard was fired for being drunk on duty and went home, put the barrel of his great-grandfather’s old U.S. Cavalry revolver into his mouth, and blew off the top of his head. He left a suicide note written in tomato sauce on his bedroom wall. It read: For sins known and unknown. That same week the file on the death of Jesus Santiago, the young Latino, vanished from Dr. Stankeviius’s locked office. When the doctor attempted to locate the boy’s record on the prison server, it was gone.

A month later, on the day of the devastation at the Royal London Hospital, Dr. Stankeviius had the guards bring Nicodemus into his office. The psychiatrist was sweating badly when he made that call.

Neither guard touched Nicodemus as they ushered him into the doctor’s office, and though they both towered over the stick-thin little man, he exuded much more power than they did. Dr. Stankeviius noted that the guards kept their hands on their belts near their weapons.

Nicodemus stood in front of the desk, his hands loose at his sides, head slightly bowed so that he looked up under bony brows at the doctor. Nicodemus had eyes the color of toad skin—a complexity of dark greens and browns. His skin was sallow, his lips full, his teeth white and wet.

“Have a seat,” offered Dr. Stankeviius. He could hear the tremble in his own voice.

“I thank you,” Nicodemus said in the oddly formal way he had. A guard pushed a chair in front of the desk and the prisoner sat. He leaned back, folded his long-fingered hands in his lap, and waited. His eyes never left the doctor’s face, and Nicodemus’s lips constantly writhed in a small smile that came and went, came and went.

“Do you know why I asked you to visit me today?” began the doctor.

“Do you?”

“What is that supposed to mean?”

“It means what it wants to mean, sir. We each derive our own meaning from life as we fly through the moments.”

“Are you aware of what has happened today?”

“I am aware of many things that have happened today, Doctor. Saints and sinners whisper to me in my sleep. Dumas speaks truth to me in my right ear and Gesmas tells only lies to my left ear. Please be specific.”

Stankeviius did not recognize the two names Nicodemus had mentioned, but he wrote them down. Then he leaned forward. “Jesus Santiago, the boy who was killed … the numbers twelve/seventeen were cut into his skin.”

Nicodemus said nothing.

“Why do you think someone did that?”

Nothing.

“Did you do that?”

“No, sir, I laid not a hand on that child. Anyone who says that I did is a liar in the eyes of the Goddess and will be judged accordingly.” ’

Stankeviius wrote down “goddess” but did not comment.

“Did you arrange to have it done?”

“What people do is theirs to explain or justify.”

“Do you know who did it?”

No answer.

“Why ‘twelve/seventeen’? Why those numbers?”

Nicodemus said nothing.

“Do you know what today’s date is?”

“Time is a pool, Doctor. Today is every day.”

“Please answer the question. Do you know what today’s date is?”

“Yes,” he answered, his writhing lips twisting as if fighting to contain a laugh. “As do you.”

Dr. Stankeviius stared at him. He licked his lips. They were dry and salty. He knew that he should end this line of conversation right now and call the warden, but he felt compelled to talk to this man.

“Did you have advance knowledge of what was going to happen today?”

Nicodemus beamed. “I am but a voice in the wilderness crying, ‘Make straight the path.’ I am neither the right hand of the Goddess nor her left hand. I am a leaf blown by her holy breath.”

The psychiatrist opened his mouth to ask about which goddess the prisoner referred to, but Nicodemus continued. “This is an important and blessed day in the history of our broken little world. Grace is bestowed upon those who witness such events. We need to lift up our voices and rejoice that we are living in such times as these. Future generations will call these biblical times, for with every breath we are writing the scriptures of a newer testament. The Third Testament that chronicles a new covenant with our Lord.”

“You mention a ‘goddess’ and you mention the Lord. Would you care to explain that to me, Nicodemus?”

The prisoner laughed. It was a disjointed, creaking laughter that rose in rusted spasms from deep in his chest. The sound of it chilled the doctor to his marrow.

“The Goddess has heard the call of seven regal voices and has awakened,” Nicodemus said softly. “She is coming. Not in judgment, Doctor, but to stir the winds of chaos with her hot breath.”

“How do you know this?” asked the doctor.

“Because I am not here,” said Nicodemus. “I am the fire salamander that coils and writhes in the embers at the Goddess’s feet.”

He did not say another word, but his eyes burned with a weird inner light that Dr. Stankeviius could not look into for more than a few seconds. After several fruitless attempts to get more information from the prisoner, the doctor waved to the guards to have Nicodemus taken back to his cell.

When he was alone, Stankeviius pulled a handful of tissues from the box on his desktop and used them to mop the sweat from his face. He tried to laugh it off, to dismiss the strangeness of the moment as a side effect of the terrible tragedy in England that was rocking the whole world. His own laugh was brief and fragile, and it crumbled into dust on his lips.

He sat at his desk for several minutes, dabbing at his forehead, staring at the chair in which the prisoner had sat. The echo of that laugh seemed to linger in the air like the smell of a rat that had died behind the baseboards. Stankeviius had been a prison psychiatrist for eleven years, and he had worked with every kind of convict from child rapists to serial murderers and, during his days as a psychiatric resident, had even sat in on one of Charles Manson’s parole hearings. He was a clinician, a cynical and jaded man of science who believed that all forms of human corruption were products of bad mental wiring, chemical imbalances, or extreme influences during crucial developmental phases.

But now …

He licked his lips again and reached for the phone to call the warden. He told him the bare facts, allowing the warden to draw his own inferences. When he replaced the receiver he continued to stare at the empty chair.

He believed—wholly and without a shred of uncertainty—that he had just encountered a phenomenon he had always considered to be a cultural myth, a label given to something by minds too unschooled to grasp the overall science of the human condition. Stankeviius had no religious beliefs, not even a whisper of agnosticism.

And yet … He was sure, beyond any doubt, that he had just met true evil.

Chapter Twelve

Barrier Headquarters

&

nbsp; London, England

December 17, 2:22 P.M. GMT

This was turning into one bitch of a day. The images of the burning Hospital were now overlaid with an image of the mocking logo of the Seven Kings and the film loops of the towers crumbling into dust on a sunny New York day. I felt enormously out of place and thoroughly impotent. The bad guys were killing people and I was taking meetings.

Jesus.

I cut out of the conference as soon as I could. They let me use an empty office so I could make some calls.

Church answered on the third ring. He doesn’t say anything when he answers a phone. You made the call, so it’s on you to run with it.

“Seven Kings,” I said. He made a soft sound. It might have been a sigh, but it sounded more like a growl.

“How sure are you?” he asked quietly.

“Very.” I told him about the video. “Deep Throat let us down on this one.”

“Yes,” he said. “By the way, did you note the time of the explosion?”

“Yep. No way it’s a coincidence.”

“I don’t believe in coincidences. Expect the newspapers to catch on soon.”

“That’s going to be a shitstorm, Boss. Is this a Kings/Al-Qaeda operation? Are the Kings showing support for Uncle Osama? Or is this some attempt to hijack the 9/11 vibe to make this one even worse?”

“All good questions in need of answers. We’ve been in a holding pattern with the Kings for months.”

“Balls,” I growled. “This is how the military must feel after more than a decade trying to find bin Laden.”

“Not all problems have quick solutions. The longer you’re in this business, the more you’ll come to know that.”

He was right. Even though my first few missions with the DMS were insanely difficult and dangerous, they had ended quickly. A few days or a week tops. I guess it’s because something has to be in motion and have gained traction before it comes onto the DMS radar, which means we usually have to fight the clock to keep the Big Bad from doing whatever it has cooked up. The Kings thing was different. It was huge but vague. It was like trying to guess the size and shape of the Empire State Building by standing four inches away from the wall at ground level. Perspective was all skewed.

Flesh & Bone

Flesh & Bone The Adventure of the Greenbriar Ghost

The Adventure of the Greenbriar Ghost Whistling Past the Graveyard

Whistling Past the Graveyard Scary Out There

Scary Out There The Wolfman

The Wolfman The King of Plagues

The King of Plagues Doctor Nine

Doctor Nine Fire & Ash

Fire & Ash The Dragon Factory

The Dragon Factory Deadlands: Ghostwalkers

Deadlands: Ghostwalkers Glimpse

Glimpse Mars One

Mars One Benny Imura 03.5: Tooth & Nail

Benny Imura 03.5: Tooth & Nail Bits & Pieces

Bits & Pieces Dust & Decay

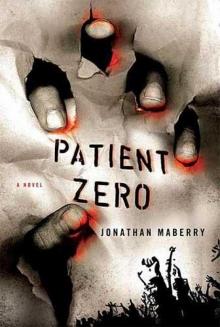

Dust & Decay Patient Zero

Patient Zero The Orphan Army

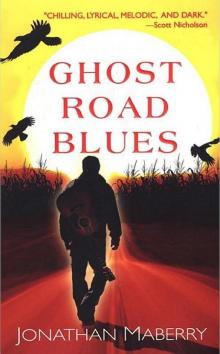

The Orphan Army Ghost Road Blues

Ghost Road Blues Vault of Shadows

Vault of Shadows Dust and Decay

Dust and Decay Rot and Ruin

Rot and Ruin Code Zero

Code Zero Kill Switch

Kill Switch Like Part of the Family

Like Part of the Family Flesh and Bone

Flesh and Bone Bad Moon Rising

Bad Moon Rising V-Wars

V-Wars Dead & Gone

Dead & Gone Fire and Ash

Fire and Ash Hellhole

Hellhole Countdown

Countdown Dogs of War

Dogs of War Pegleg and Paddy Save the World

Pegleg and Paddy Save the World Dead Mans Song

Dead Mans Song Assassin's Code

Assassin's Code Dead of Night

Dead of Night Zombie CSU

Zombie CSU Dark of Night - Flesh and Fire

Dark of Night - Flesh and Fire Aliens: Bug Hunt

Aliens: Bug Hunt Broken Lands

Broken Lands Fall of Night

Fall of Night Ink

Ink Still of Night

Still of Night Relentless

Relentless Joe Ledger 1.20 - Story to the Dragon Factory - Deep, Dark (a joe ledger novel)

Joe Ledger 1.20 - Story to the Dragon Factory - Deep, Dark (a joe ledger novel) Property Condemned (pine deep)

Property Condemned (pine deep) The Dragon Factory jl-2

The Dragon Factory jl-2 Deep Silence

Deep Silence Joe Ledger

Joe Ledger SNAFU: An Anthology of Military Horror

SNAFU: An Anthology of Military Horror Assassin's code jl-4

Assassin's code jl-4 Code Zero: A Joe Ledger Novel

Code Zero: A Joe Ledger Novel Fire & Ash bi-4

Fire & Ash bi-4 Tooth & Nail (benny imura)

Tooth & Nail (benny imura) Dead Man's Song pd-2

Dead Man's Song pd-2 Joe Ledger: Unstoppable

Joe Ledger: Unstoppable The King of Plagues jl-3

The King of Plagues jl-3 The X-Files Origins--Devil's Advocate

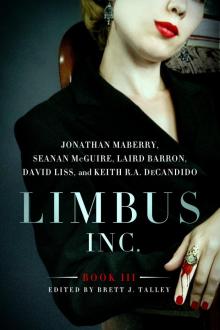

The X-Files Origins--Devil's Advocate Limbus, Inc., Book III

Limbus, Inc., Book III Ghost Road Blues pd-1

Ghost Road Blues pd-1 Patient Zero jl-1

Patient Zero jl-1 Death, Be Not Proud

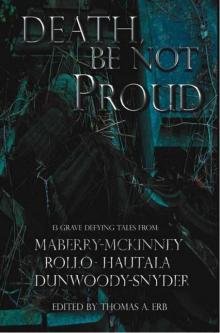

Death, Be Not Proud Countdown: A Joe Ledger Prequel Short Story to Patient Zero (joe ledger)

Countdown: A Joe Ledger Prequel Short Story to Patient Zero (joe ledger) Aliens

Aliens Extinction Machine jl-5

Extinction Machine jl-5 Ghostwalkers

Ghostwalkers Flesh & Bone bi-3

Flesh & Bone bi-3 Joe Ledger 2.10 - Material Witness (a joe ledger novel)

Joe Ledger 2.10 - Material Witness (a joe ledger novel) Nights of the Living Dead

Nights of the Living Dead Dead & Gone (benny imura)

Dead & Gone (benny imura) SNAFU: Heroes: An Anthology of Military Horror

SNAFU: Heroes: An Anthology of Military Horror Tooth & Nail: A Rot & Ruin Story

Tooth & Nail: A Rot & Ruin Story